“Her finely-touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” George Eliot

“…the unfading beauty of a gentle and quiet spirit, which is of great worth in God’s sight” 1 Peter 3:4

“Thou God seest me.” Genesis 16:13

The irony of attention seeking behaviour is that it results every time in almost certain failure. The people to whom we are drawn, whose characters attract us are often those who seem unaware of the gallery, untroubled by being unseen, unnoticed, secure enough in their own sense of self that adulation from others or even the remotest glance of interest is a matter of indifference to them.

Dorothea Brooke, Middlemarch’s heroine, is one such person and her creator’s epitaph to her at the very end of the novel is one that made a huge impression on me the time I first read it as an undergraduate English Literature student at St Andrews University in Scotland. Much about Dorothea is frustrating and positively off-putting but it’s not about her that I want to write; it’s about the value of the hidden life by definition un-noticed by the masses.

George Eliot lost her own evangelical faith and so to end her work like this is not to preach at the reader that it’s all ‘ok’ because God sees (although He does) but to recognise the fundamental and incalculable beauty of a life well lived. Seen by many or few or even none, there is worth and significance to every moment lived whether it be internal, spiritual, emotional, physical. The novelist is one who takes the trouble to observe the distinct loveliness (or not) of a given act, a movement of the hands, a cast of the eye, an awkwardness of gait, the tone and timbre of a voice, the poignancy of a hesitation, the glory of a moment of relational courage – those delights of humanity seen and known only by those who care to notice them or who have the eyes to see. Many won’t but the value of these realities is not lost.

Conversely, many, will notice our lives. God Himself certainly does. It is the desire to be noticed by the masses or even one other person that has to be slain along with the lie that one’s life must leave a visible and recognised mark to have been worth living.

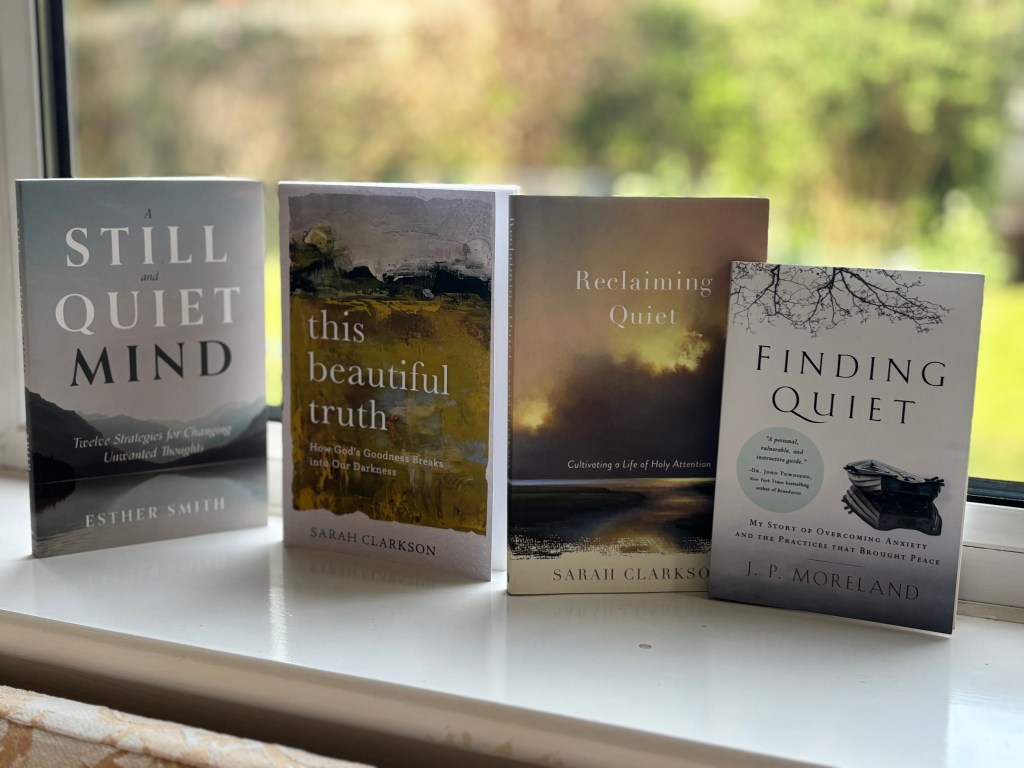

Increasingly I’m drawn to writers on the subject of the quiet life: Susan Cain, Sarah Clarkson, J P Moreland, Esther Smith, writers who acknowledge the battle that must be fought to slay the internal taunt that one must be exceptionally talented, socially accepted or widely-admired by some perceived elite to be ‘interesting’. That derisive voice speaks loudly, subtly and, I think, very unhelpfully particularly to younger minds. It can take a lifetime to dig up the roots of its pernicious weeds. God, author of authors, sees the struggle as the conflict rages.

I hope that whatever literature you’re reading, biblical or otherwise, spurs you on to persevere in living well in each unseen moment.

Leave a comment