Thoughts on Rose Tremain’s Absolutely & Forever

“When I was fifteen, I told my mother that I was in love with a boy called Simon Hurst and she said to me, ‘Nobody falls in love at your age, Marianne. What they get are ‘crushes’ on people. You’ve manufactured a little crush on Simon.”

So begins Rose Tremain’s latest novel narrated by Marianne, a delightfully ‘ordinary’, unexceptional, horse-mad, middle-class girl from the Home Counties in the 1960s, who experiences the commonest of human experiences – lost love.

At first, she and Simon seem to be getting along well but after he fails his Oxford entrance exam he flees in disgrace to Paris with dreams of becoming a writer. Marianne imagines he will wait for her and so begins her ‘sad Simon longing’.

“Love is a kind of illness, isn’t it?”

They correspond and she assiduously tries to improve her French with a view to moving to Paris herself once she finishes school. Of course, the letters become less frequent until one day she receives his last ‘which would implant the stone in my heart forever’.

“Dear Marianne,

I’m so sorry not to have written sooner, but I thought it best to wait till you got home and could read this there and not at school.

I am getting married.

My fiancée is my landlady’s daughter, Solange Louvel…Solange is expecting a child….”

The book is the story of Marianne’s unfolding life and marriage after the loss of Simon, her journey from the ‘Love Asylum’ to the ‘Grief Asylum’ and of the enduring impact of this first love.

Perhaps sharper readers than I am will have spotted the entrance of a new boy into the Sixth Form at Marlborough, where Simon is at school, Amar Nath Chatterjee, ‘cleverer than anybody else alive’. Perhaps they will have noticed how Marianne’s Scottish friend Pet acknowledges that yes, ‘Simon Hurst is beautiful’. Perhaps they will have spotted the imbalance of reciprocity between the couple, the hint that a deeper yearning plagues Simon. But Marianne does not and such is Tremain’s skill that neither does the reader. Only at the end is it plain that just as Marianne has fruitlessly longed for Simon for so many years, he too has borne his own longing…for Amar.

Marianne’s husband Hugo, whom she affectionately calls ‘Anthracite’ – (a coal like substance with a ‘sub-metallic lustre’) – perhaps in itself a pet name indicative of a distinct lack of passion in the relationship – himself endures his own longing for a more reciprocal love from Marianne who eventually leaves him after the loss of their first unborn child in a riding accident, leaving her unable to have further children.

Each of these characters carries an enduring, unfulfilled longing, the letting go of which eludes them all.

“Many waters cannot quench love; neither can the floods drown it”

Song of Solomon 8:7

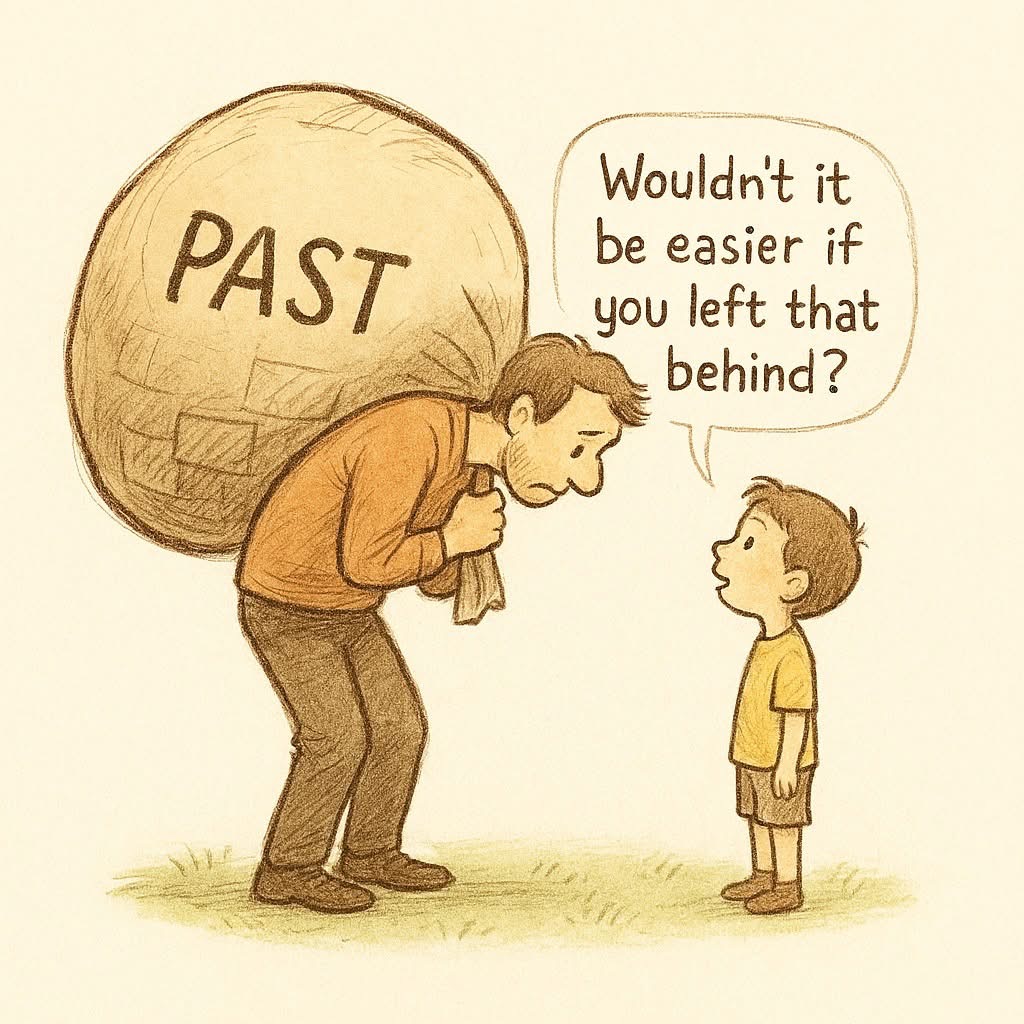

Is it possible to be addicted to a hope, a longing, a delusion even when reason, counsel and the long endurance of a draining ache render consciousness at times almost unendurable?

I came across this humorous picture online and was struck by its poignant wisdom.

Marianne, in her grief, turns to writing. She writes a charming story of a horse, Diego, loved and looked after for a while by a boy who eventually and inexplicably abandons him. Marianne works through the permutations of her story reflectively:

“I decided that Diego would manage to get out of the shed where the boy has abandoned him. He escapes by rearing up and tugging free the wooden bar to which his halter is tethered. For a long time, he runs wild on the pampas, grazing on clover, drinking from foaming little streams, but the wooden bar is still attached to the rope halter and the bar keeps striking his flesh as he moves and begins to wound him.”

Diego is soon captured by a ‘posse of rancheros’ who take him on, tend to his wound, give him fodder and shelter and put him to work. But Diego is a wise, sensitive and emotionally astute creature, as is his creator.

“The piece of wood was the last bit of proof that I’d ever belonged to the boy and it had hurt me and made a wound in my side, but now I miss it. It seems very stupid to miss a piece of wood and yet I do.”

“To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.”

― C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves

To love is to risk woundedness, abandonment, rejection, slavery even. It is then, raw and empty, that we may finally, defeated, fall on our knees. I wonder whether, in the relative wealth of the west, God uses this very real pain of lost love to draw us into His unquenchable, unconditional, eternally enduring love.

‘In the sorrows of affliction, tell your secrets to the Friend who sticks closer than a brother. Trust all your concerns to Him who can never be taken from you, who will never leave you, and who will never let you leave Him, even “Jesus Christ [who] is the same yesterday and today and forever.” “I am with you always” is enough for my soul to live upon no matter who forsakes me.’

Charles Haddon Spurgeon

Leave a comment